|

| Roger realizes a cherished childhood memory is actually a scene from an old movie |

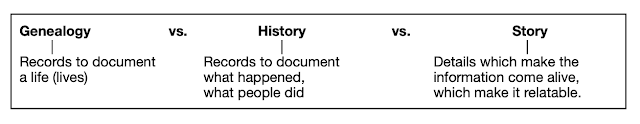

To my mind, a genealogist looks for historical records to document the people in their family trees, as especially gleaned from vital records — when they were born, baptized, married, had children, died (and more, of course).

A Family Historian, who is essentially a Local Historian, aims to find the historical records which tell us about what those people did and what happened during their time period and in the places they lived.

Historical records — facts — are merely fragments, bits of information (which are all too often incorrect, by the way). As we find these facts, we can’t help but build stories in our minds. We ask ourselves: Why would she do that? Why did they leave Germany? What was he like — was he a nice man?

And this movement from genealogy and history towards storytelling causes us to consider the tension between nonfiction (should be true) and fiction (we make it up). Much more can be said about this, of course.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This week, my husband, Bob, and I are binge-watching the TV Series Fargo, which begins each episode telling us that this story is true, and that it happened in 2006, and that the names of the survivors have been changed, but that otherwise the story is told as it happened. Of course, as you watch the TV show, you know that this is a lie, that it never, in fact, happened. But — it’s a good story, anyways.

Fargo (the TV series) is, in fact, about storytelling itself. Consider Season 1, Episode 8, and a scene which I call, “How to Build a Story.”

The new Chief and Molly (Deputy Solverson) are trying to solve several murders, including those of the former Police Chief and the wife of a local citizen named Lester Nygaard. To do so, they build stories/theories about what happened.

The Chief grabs his theory quickly and wants to believe in it because it solves problems. He does not enjoy the act of building a story. He becomes frustrated when presented with evidence which potentially negates his theory, and so he holds onto his story even when it doesn’t make any sense.

His theories are always based upon archetypal stories, which he grabs and misapplies.

It was a drifter, he says, maybe more than one, who broke into Lester’s house and killed the wife and the chief. There is not only no evidence to support this, but there is evidence to counter this.

The Chief likes the drifter story, but, eventually, he has to give in and admit that it was wrong.

What does he do then? The Chief simply believes other archetypal stories. He says that Lester’s brother killed Lester’s wife in a jealous rage because they were having an affair. (The chief just happened to be there, and that’s why he got killed.) And he continues — Lester covered for his brother because he was afraid of his brother’s temper.

Drifter. Jealous lover. Brother fearing brother. Archetypal stories.

Molly is aghast. She tries to present evidence; all she wants is to be reassigned to the case. But the Chief has already celebrated the arrest and so he shuts her down.

So Molly turns to the other, in her mind related, unsolved case, and asks about it. The Chief has also attached an archetypal story to this murder: Sam Hess was killed by his stripper/prostitute’s jealous boyfriend. It is simply another jealous lover theory, but the problem is that there is no evidence that the stripper/prostitute even had a boyfriend.

Molly is desperate to get back on the case. Not only is she a good police officer and so wants to do a good job and find the real murderer, but the murdered Police Chief was her friend, and his pregnant wife is also her friend — this case personally matters to her. She is invested.

Molly builds her stories from evidence, from the record of facts, for which she doggedly searches. To make sense of her facts, she draws the evidence on white boards (or windows), with boxes and arrows and notes and pictures. And when she tries to explain the evidence, we can see how difficult it is to create a story from fragmentary facts, how to find the relationships, the cause-and-effects, the motivations — the plot that should naturally result from the evidence.

Over time, we see how Molly builds a “working story,” but when presented with new facts which counter, she then has to look again at all the evidence, draw new arrows and boxes, make sense of it all. Bit by bit, she will get to the truth (or at least to a better truth than the Chief’s).

And one more interesting scene follows in which Molly is with her friend, the wife of the police chief who has been killed. The wife has been depending upon Molly to “stay on” the case, to make sure that the killer has been found.

The chief is still celebrating his recent arrest of the alleged murderer, and the wife expresses her relief to Molly that it’s all done now. Molly is frustrated and mutters, “But . . . the evidence . . .” She wants to say more, but she sees in her friend’s eyes that her friend needs this story, feels better believing that her husband’s killer has been found and will be punished. So Molly holds back.

The chief is still celebrating his recent arrest of the alleged murderer, and the wife expresses her relief to Molly that it’s all done now. Molly is frustrated and mutters, “But . . . the evidence . . .” She wants to say more, but she sees in her friend’s eyes that her friend needs this story, feels better believing that her husband’s killer has been found and will be punished. So Molly holds back.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Let each of us consider this business of storytelling — (1) how we build our stories, and (2) what these stories mean to others.

When we write our family stories, we want them to be true; we want to tell what really happened (a goal that perhaps can never really be reached, by the way.)

But we also want them to be good stories — entertaining stories, stories with morals perhaps.

The more I immerse myself in history (nonfiction) and stories (fiction), the more I think that nonfiction either doesn’t exist at all, or that perhaps the opposite is true — all fiction is nonfiction.

But that’s another story.

No comments:

Post a Comment