This week I am reading a biography of the songwriter Paul Simon (Robert Hilburn, Paul Simon: The Life, Simon & Schuster, 2018), which has inspired creative thoughts regarding this business of fiction and nonfiction. In my post yesterday, I suggested that either, or perhaps both, of the following contradictions are true:

Consider the song, “Like a Bridge Over Troubled Water,” with its sad and soothing, and ultimately hopeful, lyrics. Paul Simon, who was known for being slow in writing and recording new music, describes this song as flowing through him, quickly and beautifully.

He also states that the opening lines were memoir: “I like the first lines of a song to be truthful, and those were . . . I was feeling weary because of the problems with Artie [Art Garfunkel, Simon & Garfunkel] and other things. I was also feeling small. But then the song goes away from memoir. It comes from my imagination” (143).

Simon further describes how his own awareness of himself helps him to be empathetic with others: “I’ve always been able to feel what it’s like to be on the outside even though I’ve kind of been at the center of things in my own life” (143).

When you’re weary, feeling small

When tears are in your eyes

I will dry them all

I’m on your side

When times got rough

And friends just can’t be found

Like a bridge over troubled water

I will lay me down

Like a bridge over troubled water

I will lay me down

When you’re down and out

When you’re on the street

When evening falls so hard

I will comfort you

I’ll take your part

When darkness comes

And pain is all around

Like a bridge over troubled water

I will lay me down

Like a bridge over troubled water

I will lay me down

All of this is lovely and perfectly understandable. But then he describes the third verse, which came to him, also quickly, but much later in time, just as Simon & Garfunkel were in the studio ready to record the song. This verse is one which has often perplexed listeners.

In 1970, when I was 12 years old and this song was a hit, I loved Simon & Garfunkel. I played their music on the piano, and sang (for no one, in my living room). That third verse, though — didn’t know what it was about, but it was nice, and fun to sing.

This week, while reading this book, and learning the autobiographical impetus to that third verse, I’ve reread this verse over and over, and spoken it out loud, and shivered, and felt immense gratitude to Paul Simon.

Here’s what he tells us. The morning before coming into the studio, Paul Simon’s soon-to-be wife found grey hairs in her head and was deeply upset. This experience was on Paul’s mind when he wrote these lyrics:

Sail on, silver girl

Sail on by

Your time has come to shine

All your dreams are on their way

See how they shine

If you need a friend

I’m sailing right behind

Like a bridge over troubled water

I will ease your mind.

Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhh. While I loved the song anyways without knowing this meaning, I love it so much more now. It has a story!

Admittedly, I wouldn’t have identified much with that story in 1970, at 12 years old. However, today, I can’t even begin to describe the beauty. To think that in 1970, a man would have written a song to an aging woman (or, at least, a woman who felt she was aging) to show her that the best part of her life is still to come — gosh, wow.

Well, I think I can say that in 1970, this was not an oft-heard message. And, today, yes, things are much better, but, still, this is a great message to hear. I’m 62 years old, and I can tell you that Paul Simon was right — Our time has come to shine, and our dreams are on their way, and we only have to allow ourselves to see it. And we might not be as alone as we think.

We don’t always need (or have a right) to know the autobiographical underpinning of a creative piece. But, in this case, knowing it has transformed the song for me.

But, you might ask: Lisa, is the song nonfiction? Is it fiction? Or is it neither? Or both?

And what about our TV Series Fargo (written about in yesterday’s blog post)? Well, that’s easy, that’s fiction, baby, pure fiction. Right? The people are made up and exaggerated; the setting is in a real place but seems fantastical. The plot is not only made up, but is also, in fact, ridiculous. Still, it’s well-written and it’s unbelievably well-filmed and acted.

And here’s what it’s telling us overall:

This writer (Noah Hawley) wanted to say that; he had a reason to say that; that reason certainly springs from real life. If we knew more about his life, we would probably understand what he saw or experienced that caused him to want to write a show which delivers this message.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

It’s a silly thing, really, this effort to try to make something this or that, fiction or nonfiction. And who cares — if we like it, we like it.

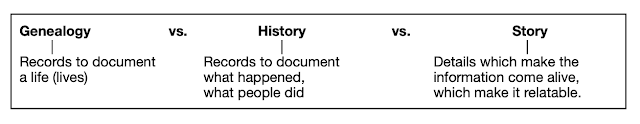

But for those of us writing about real people, it is something we think about all the time.

I’m writing a book about my ancestors in Rochester. The history of these people, and the places they lived, and the times they lived in, is intensely researched. The backbone of my book is based upon vast historical records. Nonfiction.

However, I’m drawing these people as characters. I’m attempting to create the characters as close as I can to what I think they were like, based upon the historical information I find. But there’s always an element of guesswork, especially when it comes to character. How can I be sure that they were really like this? Maybe I’ve got it wrong.

Furthermore, I’m creating scenes here and there. In

|

Otto center, top row, with his family, circa 1905

(photo courtesy Gary and Jacque Fraser) |

fact, I’m creating a break-up scene with Otto and Emma, who had a short-lived, tragic marriage, begun in 1887, and over by 1889. I don’t, in fact, know where they broke up or how they broke up. But I know where they lived, and I know what it looked like at that time, and I know the factors that probably led to the breakup (and what happened afterwards), and I know approximately when they must have seen each other for the last time. And so I’m making up a scene, set in NYC, on a specific street and in a specific building. It dramatizes them, helps us to feel them as people who once actually lived. It seems the right thing to do.

I hope I’ve got it right. But I might be wrong.

Most of the book will be straight from history — history is so fascinating that you really don’t have to add to it or make it up. Most of the book is true (hopefully). But some of it is guesswork.

Am I writing fiction, or nonfiction?