NOTE: This blog entry is part of a collaboration with a wonderful blogger on Rochester, New York, history. The blog is Gonechester, and the writer there, Geoffrey Zeiner, has chronicled his own research on my great-great grandfather, Mathias Dossenbach. Here is a link to his blog entry: Gonechester: Mathias Dossenbach - Block By Block. Geoffrey's research and writing is remarkable -- I am learning so much about the buildings and addresses that will help me put Mathias's life and efforts into greater context.

In the comments, would you please let me know about what you think about this collaboration? Thanks!

Also, You can read Part 1 of this topic -- My Immigrant -- It follows below, and is also listed on the right side of this blog. Enjoy!

Part 2: The Dossenbachs in Rochester, New York

|

| Probably Matthias and Regula Dossenbach, circa 1865-1869 (Courtesy Polly Smith) |

In Part 1 of this blog, we followed My Immigrant’s path from Baden, where Mathias Dossenbach’s family had lived for generations, to western New York, southern Canada, and eventually Rochester. We felt Mathias’s frustrations as he struggled with a strange language and attempted to earn a living, while also beginning a new marriage and growing a family.

|

| 1872 German Immigrants in the United States |

Mathias’s arrival in the United States in 1851 was part of a huge wave of German immigrants, which continued throughout the 1850s. In 1855, 1 in 7 Rochesterians were German-born, and the trend continued throughout the 1800s, doubling in the 1870s and tripling by 1890 (McKelvey, “The Germans of Rochester: Their Traditions and Contributions,” Rochester History, 1958). In fact, the 1900 census showed that German-born peoples, and their descendants, were the largest single ethnic group in the American population.

.png) |

| 1870s Rochester, New York (Courtesy Roch City Hall Photo Lab) |

When the Dossenbachs arrived in Rochester, New York, in late 1872 or early 1873, they found a bustling city, rich with German immigrants from the North and South of Germany -- Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish, each group forming their own enclaves while also contributing together to the Rochester economy and social scene, which included the Germania Singing Society, the German Harmonic Society, the Maennerchor musical society, the Liedertafel, the Schiller Society, all giving public concerts in Corinthian Hall and also Turn Hall on North Clinton, later renamed Germania Hall. Perhaps the musical Dossenbachs enjoyed the festivals, musicales, masked balls, bands, and street parades.

How thrilled the Dossenbachs must have been to discover that they could both celebrate their own heritage and speak their native German language, while also endeavoring to become a Rochesterian-American. Rochester was abundant in German newspapers - the Daily Beobachter, the weekly Beobachter am Genesee, the Der Anzeiger des Nordens, and a few years later, the Volksblatt and Abendpost.

By the time the Dossenbachs arrived, Rochester’s German immigrants had already founded churches and schools, where their children could learn both their new English and their parents' German language: St. Joseph’s parish school, the German Lutheran Schools, the B’rith Kodesh Temple, and the Realschule, offering a new and experimental kindergarten.

Economically, the German immigrant population formed breweries and fermentation and ice companies; established shoe/clothing/tailoring businesses, Jewish primarily, in storefronts along the north edge of the Main Street bridge, with much of the work done at home within families; grew world-recognized nurseries and optics companies; built farms, some raising pigs and others raising cows and producing butter; and, as well, worked as carpenters/masons, cabinet makers, button and basket producers.

In the 1870s, the Dossenbachs could have purchased insurance from the German Insurance Company, and by 1884, they could deposit their money in the German-American Bank. As well, neighborhoods specific to German life flourished throughout the city:

"The Germans set up scattered colonies on the fringes of the city -- places like Dutchtown (also called 'The Basket Hole' because so many Teutons made willow baskets in their woodsheds and peddled them). Dutchtown, loosely bounded by Lyell Avenue, Hague and Jay Streets, was known for its competitive baseball and football teams too. The Butter Hole in the North Clinton-Avenue D area was named for German residents who kept cows on small farms and produced the city’s butter. Swillburg in the Clinton-South Avenue area was where German settlers fed swill to their pigs and scooped rich silt from Clinton’s Ditch for their gardens. Eventually, the comfortable, plain German cottages, each with its neat yard and well-tended garden, passed to immigrants of the next wave" (Elizabeth Brayer, Our Spirit Shows: Rochester Sesquicentennial 1834-1984).

Like many newcomers to a new city, the Dossenbachs moved quite a bit, and their locations are, in fact, a travelogue of German immigrant experience in Rochester. Their earliest addresses are in the northeast of Rochester, near to Baden Street (though there was no Baden Park at that time).

|

| From Google Streetview 2013 |

In 1873, the Dossenbachs lived at 4 York Street; one year later, we find them at 107 Hudson Street; and from 1875-1877, they made their home at 17 Vose Street. The house at 17 Vose Street existed into the 1960s, and as remembered by people from that neighborhood, it looked just like this little white house in the bottom corner. In 1875, Mathias and Regula had 7 children and also took in a relative’s son, so there were 10 people living in that little house.

The proximity of these addresses was also important for some of the musical performances. On November 2, 1876, the Dossenbach family performed at the North Street German Methodist Church, not too far south from where they lived at the time. Just a few years earlier, a young man who took violin lessons from Mathias described the family playing together: “Mrs. Dossenbach played the bass viol, her sister the ‘cello, and the two daughters played first, and the little boy (about six years old) and I tried to play second. The lad was so small he had trouble holding his violin while playing” (E. C. Theilig, Hermann Dossenbach Collection, UR RBSCP).

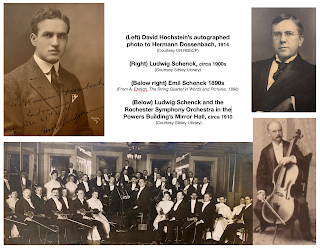

This is significant because, in fact, it was not at all unusual that immigrant families, especially German immigrant families, played instruments together. In Rochester, for example, there was the Schenck, Minges, Marthage, Appy, and Perkins families, and a couple of decades later, there were the Hochsteins.

From 1878 to 1879, the Dossenbachs moved nearer to downtown, 81 Joiner Street. This may have been because in 1879 Mathias attempted to open his own comb manufacturing business, at 149 North Water Street. While the family enjoyed music together, and Otto’s musical career flourished immediately upon arrival in Rochester, then as now, music didn’t pay the bills, and so Mathias still struggled to provide for his family. I don’t know the extent of his business or how long it lasted, and I haven’t found any further evidence of Mathias working as a combmaker.

The following year, 1880, brought a significant change for the Dossenbach family, as they moved to the southwest of Rochester, to the tree-lined streets of the Ellwanger-Barry neighborhood, today’s South Wedge, where the family would be closer to the many German musical activities and venues (mentioned above). For the next 12 years, Mathias and Regula raised their family on Sanford St (first at 66, then 93). Perhaps they were able to accomplish this with the help of their children, as was also common in struggling families of the time, especially immigrant families. The 1880 census shows Mathias as a musician, along with his son Otto, but also daughter Hermina worked in knitting rooms, and cousin Albert (listed as a son, but I don’t think this is accurate) was a carpenter. The rest of the children were either at home doing housework or at school. In 1880, the Dossenbachs’ family was complete, with the birth of their youngest child, Bertha, who was 3 years old.

In his home country of Baden, Germany, Mathias’s dream may have been freedom, but in his new homeland in New York State, his dream was that his children would become successful musicians and conductors. He watched his son Otto’s immediate success in Rochester and beyond, where Otto was known as Rochester’s “wonderful boy violinist,” followed by his son Adolph’s success, also as a violinist.

But, sadly, Mathias would only experience his first two sons’ accomplishments, for Mathias passed away in 1887, at 72 years of age. He was buried in nearby Mount Hope Cemetery. Six years after his death, Regula moved the family to her final location at 6 Nicholson Park (across the street from today’s German House), still in or near to the Ellwanger-Barry neighborhood, where she continued to live, with some of her grown children, until her death in 1906.

Regula lived long enough to see her son Adolph become the Musical Director of the Lyceum Theatre; and her son Hermann form and conduct the Dossenbach/Rochester Orchestra, a precursor to today’s Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra; and to see her son Theodore found and direct the Rochester Park Band, renowned throughout western New York; and also her daughter Hermina, who taught piano out of a studio from the home, even into the early 20th century.

However, neither Regula nor Mathias lived to see Hermann and Theodore perform with the quintette at George Eastman’s mansion from 1905-1919, and they both missed Hermann’s cofounding of a music school on Prince St, which George Eastman purchased for the University of Rochester to create the Eastman School of Music. They did not get to visit their children’s homes in the Park Avenue neighborhood, at 61 Dartmouth Street and 28 Upton Park.

Consider the span of a human life — Mathias had within his memory that vision of his little hamlet of Rheinweiler within walking distance to the Rhine River. He knew about war and failed revolutions. Mathias loved and lost and left much behind, but then reinvented himself in a new land, and loved again.

Let us, who are here today, remember him, and Regula, and their children, the children of immigrants. And especially, let’s applaud the music, which at the turn of the twentieth century, was the soundtrack to everyone's activities, and to which Mathias made his brave contribution.

Bravo, Mathias, bravo!

%20with%20Dossenbach%20addresses.png)

%20in%20Lancaster,%20Erie%20County,%20with%20different%20wife:child.png)

.png)